Economic Growth is the Anti-Poverty Strategy That Actually Works

A version of this post was published in Business Day on January 10, 2023.

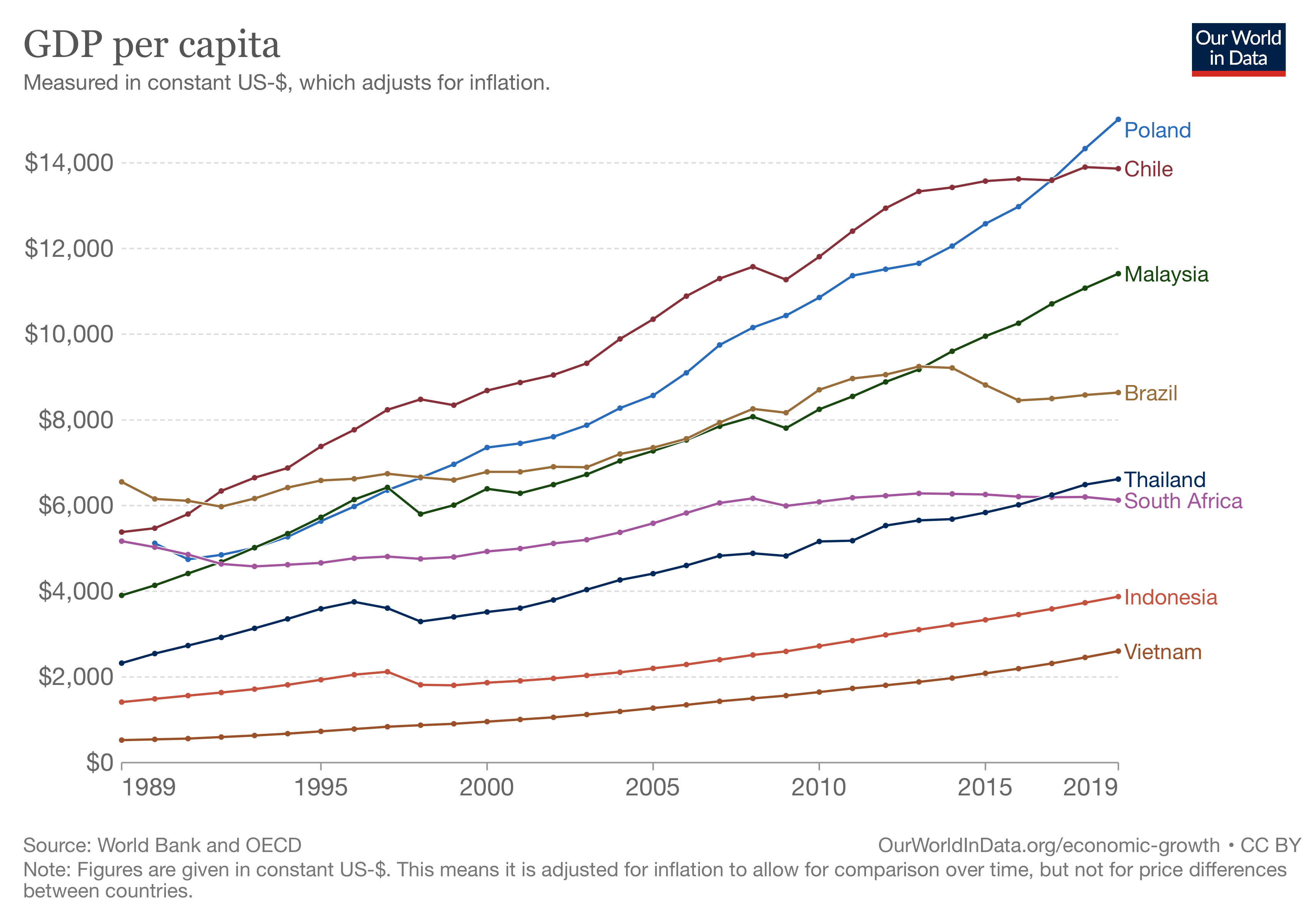

A common way of measuring economic growth is by tracking changes in GDP per capita. While there are important and well-known omissions from this measure - if environmental damage is unpriced, for example, or if there are changes in the value of work done in the household (think child-rearing or home-cooked meals) - it still captures, in a way that is comparable across countries and over time, average living standards.

Now, it is true that growth in average incomes does not guarantee that everyone will benefit equally - some people will get rich before others, after all - but are there any real examples of growth making poverty worse?

Well, no, not really. Here is a quick and dirty way to get to this conclusion: go to the wonderful website Our World in Data and play around with their interactive data visualizer. I picked six developing countries - Malaysia, Poland, Chile, Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia - that have had strong growth in the last 30 years. Note that these countries have quite different cultures and histories, and started off at quite different levels of development.

If you plot those countries’ GDP per capita from 1989 - 2019, you’ll see that indeed, their growth performance has been strong - the average Polish person’s income tripled over this period, while the average Vietnamese person’s increased by an astounding factor of five. South Africa’s real GDP per capita increased by only 18% over this period (from USD 5 169 to USD 6 125, in constant 2015 dollars) - an average growth rate of 0.24% per year.

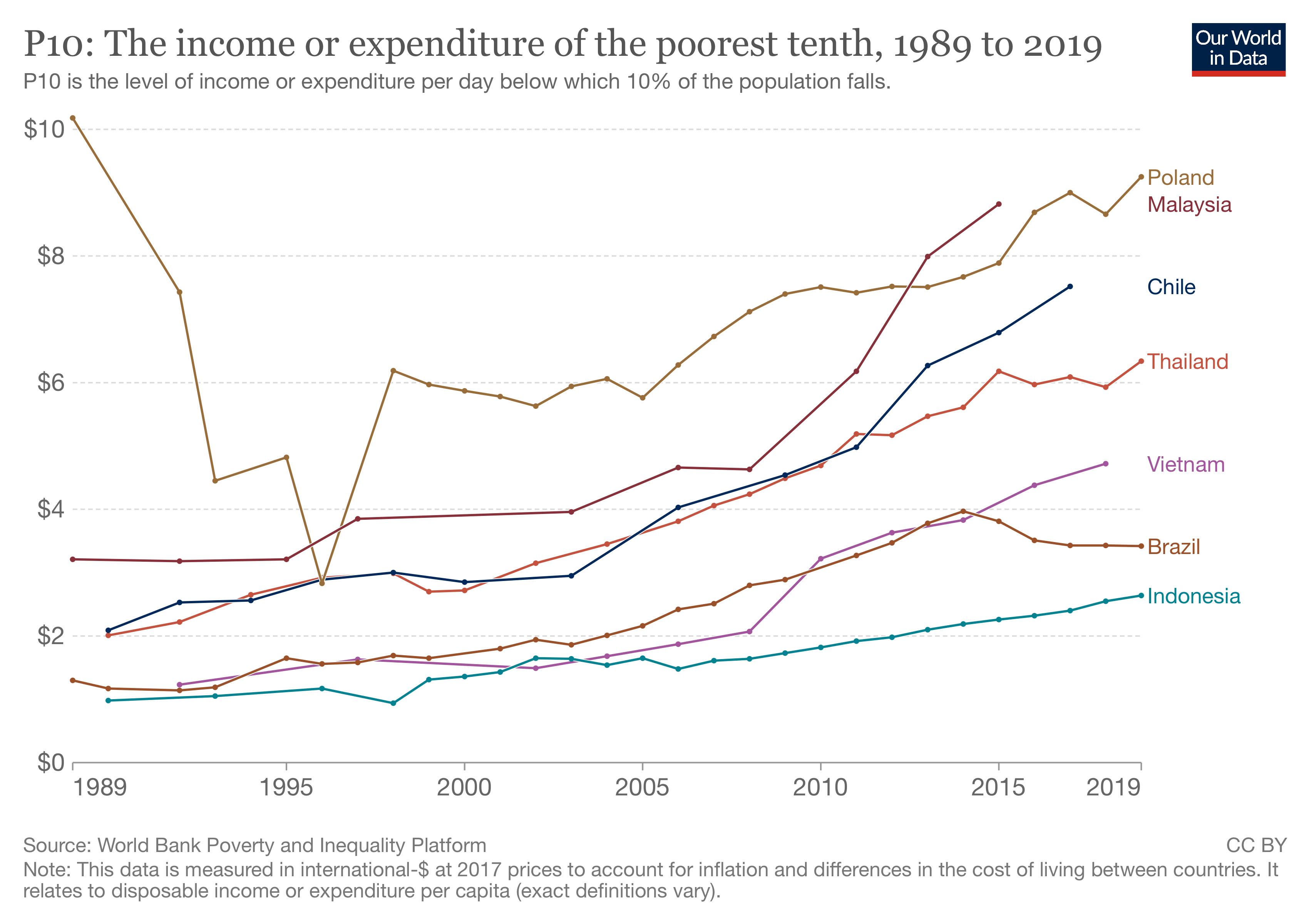

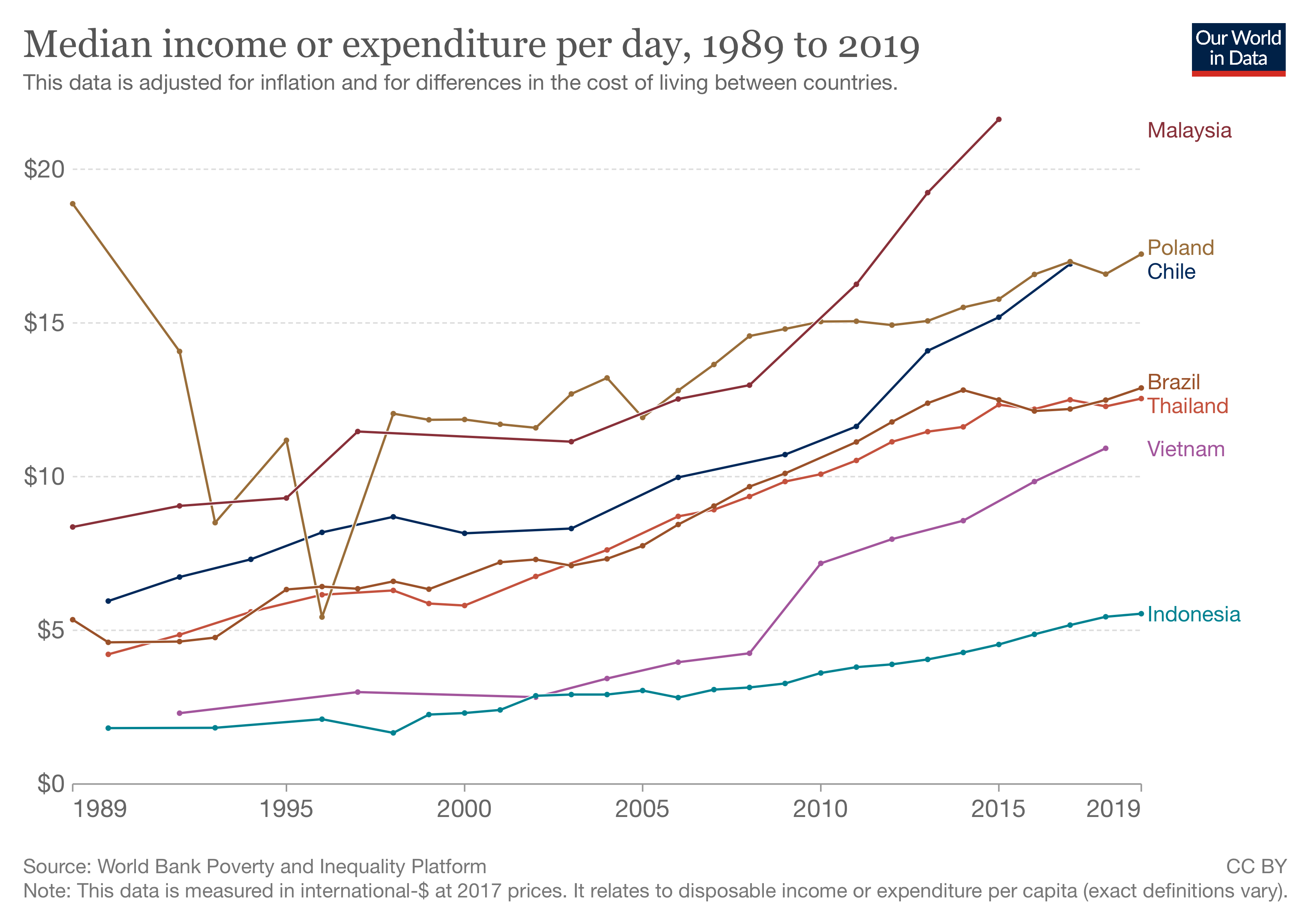

But how have the poorest people in those high-growth economies done? Did all of the gains from this incredible period of growth go to the wealthy? Again, the answer is no. While obviously poverty has not disappeared, these high-growth countries have lightened some of its most extreme burdens. The poorest 10% in Vietnam went from consuming the equivalent of USD 1.23 (in 1992) to USD 4.72 (in 2018). In Malaysia, the bottom 10% nearly tripled their consumption.

And at the median, things were even better: the median Vietnamese person experienced a quintupling of their consumption, from USD 2.31 to USD 10.92. For Malysia, the median person’s daily consumption nearly tripled (from USD 8.36 to USD 21.62). The story is much the same across all these countries, with the interesting exception of Poland, where the collapse of communism seems to have hurt the poor in the early 1990s, but subsequent growth has made up the lost ground.

These statistics can seem dry and abstract, but think about the changes in the lives of so many millions of people that these numbers represent. They mean better nutrition for children and the lowering of many of the related risks of disease and injury. They mean better lighting and heating in the home, higher-quality furniture, warmer and more durable clothing, and the easing of many other daily frustrations. They mean, in short, an increase in the quality of people’s lives.

Yes, an increase from USD 2.31 per day to USD 10.92 per day does not abolish all hardships - far from it. But these incremental gains, multiplied by millions of people and sustained over many years, are the only way that humanity has ever “made poverty history”.

You might think that ending South Africa’s economic stagnation would be a high priority for the government, but if you read the annual reports of various public-sector agencies, there is always a caveat: policymakers only want “inclusive” growth. Why isn’t growth - any growth - good enough? The DBSA’s website says “inclusive economic growth requires a shift in trajectory to ensure that it benefits every citizen in all communities equally”. The Treasury’s 2019 manifesto on the country’s “economic strategy” insists that “economic growth must be accompanied by a reduction in inequality”. You can find the phrase littered across the executive summaries of many government reports, or in the mission statements of e.g. the DTIC or the Competition Commission.

It is certainly true that growth does sometimes come with increases in inequality, as in the US throughout the 1980s and 1990s. But not always! Income inequality fell in much of continental Europe during the long postwar expansion, and more recently, Chile has had strong growth and falling inequality.

In any case, so what? If poverty is falling quickly, I cannot bring myself to care whether Christo Wiese buys an extra yacht. Let’s ask whether growth is pro-poor, rather than whether it is “inclusive”. And the historical record shows that, indeed, growth does reduce poverty.

Besides, we already have ways to ensure that the benefits of growth are shared broadly: progressive taxation, social grants, and - at least in principle - public-sector services (although in many cases the main beneficiaries of taxpayers’ money seem to be the Range Rover dealerships of Sandton). But generous transfers and high-quality public services are only possible when the economy is productive enough to pay for them. South Korea and Japan did not go from poor countries to rich ones by redistributing more aggressively in the 1960s. Growth is the only way out of poverty that actually works.

The political obstacles to pro-growth policies are bigger and more serious than mere confusion about terminology, of course. But by sneaking in a lot of tangentially related goals into the discussion, the terminology of “inclusive growth” muddies the waters, and helps preserve the status quo. (If everything is a priority, then nothing is.) Yet even a cursory look at the facts shows that rapid growth, and the reduction in poverty it brings, is possible - even in South Africa. We shouldn’t lose sight of that.